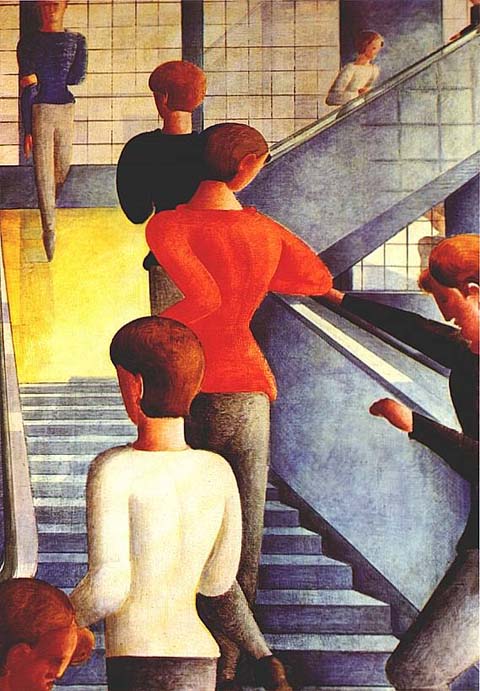

Went back to watch another hour of Christian Marclay's Clock today. Very wittily, at 4:45 p.m. Marclay has a clip in which a museum is being closed in that way that museums that close at 5 really start closing at 4:45 -- wittily because just then a stentorian guard came in to intone, over the movie (which kept playing) that it was 4:45 and the museum was about to close and we'd have to make our way towards the exits. Art museum life imitates art museum art! Like that Oskar Schlemmer painting of the Bauhaus stairway hung on the wall of the very similar stairway at the old MOMA:

Anyhow, what I noticed this time: how well the cuts between scenes were made, so that there was a quasi-narrative going on (a person made a call at 4:12, a person picked it up a call in the next scene) - effect intensified by sound-bleeds from cut to cut (sometimes anticipating, sometimes lagging the cut).

Quasi-narrative is film's stock-in-trade. Film relies on the horizon of working memory, on coherence over the last minute or so, without much concern for what's over the horizon. (Memento is an exemplary demonstration of and inquiry into this idea.) Sure, most narrative films can be recollected later as more-or-less coherent narratives. But on the middle levels, the way scenes put people together or tear them apart, can only make sense if we forget that not one minute earlier everything was terrible, or everything was fine. And on the larger levels, many a movie is just as incoherent (cf. The Big Sleep): movies can afford to be. The Clock gives you a kind of mosaic of narrative, in working-memory-long clips.

This also made and makes cross-cutting work: as I said before, we recur to some narratives in which time is of the essence. We check back every time some character is also checking back. One of those today -- a chess game at a cafe with one of the players watching the tensely photographed clock, awaiting the murderer of the other, perhaps -- turned out to go on for at least half an hour in real time. No doubt in the original film, which I didn't know, the scene lasted more like three minutes, though also, it must be, with cross-cuts that we didn't get to see. (I think probably that there were no cross-cut clips in The Clock, that every cut to another location was Marclay's, not the source's.)

I also noticed the obvious but deep fact that every film in The Clock was fictional. This makes an interesting difference: it means that at no point can we infer what time it was in reality on the day the film was shot. (This is probably not strictly true: there must be location shots with real clocks in them. But still, the principle of the thing:) All the clocks and watches depicted fictional times. Sure, they might accidentally correspond to real times, just as there might accidentally and unknown to Doyle be a real Sherlock Holmes (David Lewis's example), who did and acted just as Doyle's fictional one did. But Doyle would not be referring to this one, and these clocks would not be referring to real time. But in our world they do, since The Clock is a clock, and you always know what time it is.

You know what time it is in the theater, though you may not know what time it is in the fiction. This is because in the sequence I saw today, some of the clocks were stopped. In a museum (perhaps the one that shooed people out at 4:45, but I don't think so), two characters look at a collage comprising pornographic magazine photos and photos of clocks, all showing the same time (the time The Clock is telling). Later a character comes in to find that his clock has been smashed. We can see when. It's the time on our watches. But clearly the clock has stopped long before. (And later there's another clip, Sound-and-the-Fury-ish, with a stopped watch and broken crystal, though I think maybe we see its owner breaking it with a hammer.) I wonder whether Marclay has the scene from Chinatown where J.J. picks up the crushed pocket watches he's placed under Mulwray's tires to see when he drove off. I wonder again - well, that's what the movie makes you do - whether Hitchcock winding the clock in Rear Window appears.

So what that made me realize is how much the movie is about clock- and watch-faces. How much, again, it's about movies themselves, and in particular watching movies, watching faces, looking at the photographed face. Hitchcock's joke in the Mt. Rushmore scenes of North By Northwest and Marclay's is about the fact that movies show faces on screen at unprecedented sizes: human and clock faces. (Well, Big Ben may be as big as any photographed clock, I guess.)

As Gloria Swanson put it in Sunset Boulevard: "We had faces!"

Showing posts with label The Clock. Show all posts

Showing posts with label The Clock. Show all posts

Saturday, November 12, 2011

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

Clock-watching, or Truth, sixty times an hour

In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant offers some "axioms about time in general":

At any rate, I thought about some of this when I spent a couple of hours at Christian Marclay's The Clock, the real-time exhibition to end all real-time exhibitions.

As everyone knows, Marclay spliced together bits of film totaling twenty-four hours, each bit containing somewhere a (legible) clock, whether a digital sign like the one above, a wrist-watch, a sun-dial (I'm guessing: I don't think I saw one), or someone telling someone else the time. Some movies, parts of some scenes, appeared more than once -- if a character worried about the time keeps looking at his watch in some movie, his watch may appear more than once in that movie, as time hurries by or seems to drag on forever. Since most movies aren't in real time even when they're showing continuous time, the time difference between those clips is different (and more accurate) in The Clock from what it was in the original.

In His Girl Friday about twenty minutes passes on the clock in the twelve real minutes that Hildy and Walter are talking; in 24 the commercials allow for elisions but also compress the time a little bit so that particular deadlines can be met during the show and not during the ads. As far as I know High Noon is in genuine real time, as is Robert Wise's great boxing movie "The Set-Up" (1949).

You can certainly set your watch by The Clock, and one of the interesting parts of the experience is knowing what time it is as you watch; you don't have to worry about checking. Watching is checking. And yet you kind of forget that also: the fragments are all so gripping that you're hooked -- 60 times an hour. We regret leaving every scene for the next, or would regret it if the next scene weren't so immediately compelling. The movies!

Part of being gripped, though, is looking for the watch or clock or time-piece in each scene. (It's a pleasure to see clocks you recognize from the real world. My watch was there! (Someone trying to pawn it for drugs, at just about 1:17 p.m. Kind of early in the day, come to think of it; must have been a heroin addict.) My grandmother's clunky alarm clock! So we watch (!) somewhat differently from the way we would the original movie. It might therefore seem surprising that we're hooked, scene after scene.

And yet in another way it's not surprising. The experience is decontextualized, in the best possible sense, the way movie trailers decontextualize the scenes they show. We get little fragments of intensity, all the more intense for being unexplained, unassimilated to some reasonable desire or goal or way of making oneself secure in the world, the goal of all characters in sequential narration.

Sequence again, then. The Clock quilts together scenes from a century or so of movies. We're not looking at the sequential unfolding of time. We're looking at different spaces, maybe 2,880 of them (the clips are not the same length; they probably average thirty seconds apiece, but who knows?) that are not simultaneous, and different times that are not sequential, but all brought to the spatial simultaneity, the spacial equivalent of simultaneity, on the video screen. Time and space are made mosaics of each other. We recognizes bits and pieces -- here a scene, there some sort of time-keeper. They all come together. It's beautiful.

Time has only one dimension; different times are not simultaneous but sequential (just as different spaces are not sequential but simultaneous).... Different times are only parts of one and the same time.... the proposition that different times cannot be simultaneous could not be derived from a universal concept.... Hence it is contained directly in the intuition and presentation of time. --Pluhar's translation, A32 = B48Sequence is how time is related to counting, which is to say that time can be measured by a numbering clock always counting upwards. Einstein's thought experiments about time really consist of showing the kinds of things that can act as clocks: viz., any physical system that follows the then recently articulated fundamental axioms of arithmetic: the idea of a defined interval and the idea of a succession of such intervals. (Thus two mirrors bouncing light back and forth to each other are a clock.) Since pretty much all things can be clocks (movies pre-eminently, ticking at 24fps), the universe of things is a universe subject to time. (The fact that Einstein proved Kant wrong is not really germane here: what matters is the domain that space and time map out.)

At any rate, I thought about some of this when I spent a couple of hours at Christian Marclay's The Clock, the real-time exhibition to end all real-time exhibitions.

As everyone knows, Marclay spliced together bits of film totaling twenty-four hours, each bit containing somewhere a (legible) clock, whether a digital sign like the one above, a wrist-watch, a sun-dial (I'm guessing: I don't think I saw one), or someone telling someone else the time. Some movies, parts of some scenes, appeared more than once -- if a character worried about the time keeps looking at his watch in some movie, his watch may appear more than once in that movie, as time hurries by or seems to drag on forever. Since most movies aren't in real time even when they're showing continuous time, the time difference between those clips is different (and more accurate) in The Clock from what it was in the original.

In His Girl Friday about twenty minutes passes on the clock in the twelve real minutes that Hildy and Walter are talking; in 24 the commercials allow for elisions but also compress the time a little bit so that particular deadlines can be met during the show and not during the ads. As far as I know High Noon is in genuine real time, as is Robert Wise's great boxing movie "The Set-Up" (1949).

This is from The Set-Up, at the end, and,

for all I know, from The Clock

You can certainly set your watch by The Clock, and one of the interesting parts of the experience is knowing what time it is as you watch; you don't have to worry about checking. Watching is checking. And yet you kind of forget that also: the fragments are all so gripping that you're hooked -- 60 times an hour. We regret leaving every scene for the next, or would regret it if the next scene weren't so immediately compelling. The movies!

Part of being gripped, though, is looking for the watch or clock or time-piece in each scene. (It's a pleasure to see clocks you recognize from the real world. My watch was there! (Someone trying to pawn it for drugs, at just about 1:17 p.m. Kind of early in the day, come to think of it; must have been a heroin addict.) My grandmother's clunky alarm clock! So we watch (!) somewhat differently from the way we would the original movie. It might therefore seem surprising that we're hooked, scene after scene.

And yet in another way it's not surprising. The experience is decontextualized, in the best possible sense, the way movie trailers decontextualize the scenes they show. We get little fragments of intensity, all the more intense for being unexplained, unassimilated to some reasonable desire or goal or way of making oneself secure in the world, the goal of all characters in sequential narration.

Sequence again, then. The Clock quilts together scenes from a century or so of movies. We're not looking at the sequential unfolding of time. We're looking at different spaces, maybe 2,880 of them (the clips are not the same length; they probably average thirty seconds apiece, but who knows?) that are not simultaneous, and different times that are not sequential, but all brought to the spatial simultaneity, the spacial equivalent of simultaneity, on the video screen. Time and space are made mosaics of each other. We recognizes bits and pieces -- here a scene, there some sort of time-keeper. They all come together. It's beautiful.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)