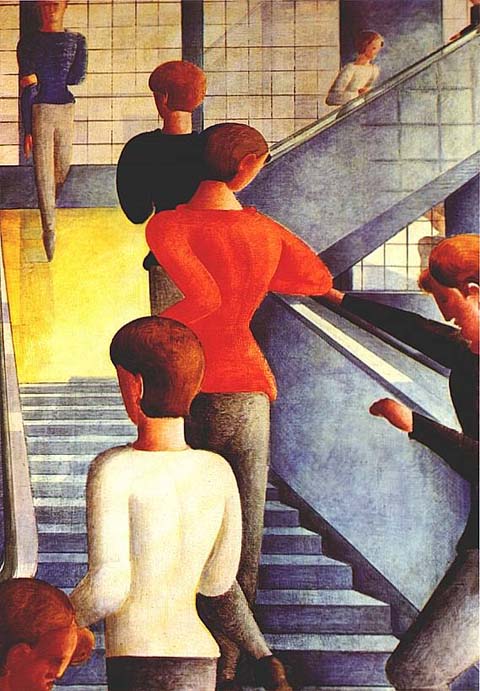

Went back to watch another hour of Christian Marclay's Clock today. Very wittily, at 4:45 p.m. Marclay has a clip in which a museum is being closed in that way that museums that close at 5 really start closing at 4:45 -- wittily because just then a stentorian guard came in to intone, over the movie (which kept playing) that it was 4:45 and the museum was about to close and we'd have to make our way towards the exits. Art museum life imitates art museum art! Like that Oskar Schlemmer painting of the Bauhaus stairway hung on the wall of the very similar stairway at the old MOMA:

Anyhow, what I noticed this time: how well the cuts between scenes were made, so that there was a quasi-narrative going on (a person made a call at 4:12, a person picked it up a call in the next scene) - effect intensified by sound-bleeds from cut to cut (sometimes anticipating, sometimes lagging the cut).

Quasi-narrative is film's stock-in-trade. Film relies on the horizon of working memory, on coherence over the last minute or so, without much concern for what's over the horizon. (Memento is an exemplary demonstration of and inquiry into this idea.) Sure, most narrative films can be recollected later as more-or-less coherent narratives. But on the middle levels, the way scenes put people together or tear them apart, can only make sense if we forget that not one minute earlier everything was terrible, or everything was fine. And on the larger levels, many a movie is just as incoherent (cf. The Big Sleep): movies can afford to be. The Clock gives you a kind of mosaic of narrative, in working-memory-long clips.

This also made and makes cross-cutting work: as I said before, we recur to some narratives in which time is of the essence. We check back every time some character is also checking back. One of those today -- a chess game at a cafe with one of the players watching the tensely photographed clock, awaiting the murderer of the other, perhaps -- turned out to go on for at least half an hour in real time. No doubt in the original film, which I didn't know, the scene lasted more like three minutes, though also, it must be, with cross-cuts that we didn't get to see. (I think probably that there were no cross-cut clips in The Clock, that every cut to another location was Marclay's, not the source's.)

I also noticed the obvious but deep fact that every film in The Clock was fictional. This makes an interesting difference: it means that at no point can we infer what time it was in reality on the day the film was shot. (This is probably not strictly true: there must be location shots with real clocks in them. But still, the principle of the thing:) All the clocks and watches depicted fictional times. Sure, they might accidentally correspond to real times, just as there might accidentally and unknown to Doyle be a real Sherlock Holmes (David Lewis's example), who did and acted just as Doyle's fictional one did. But Doyle would not be referring to this one, and these clocks would not be referring to real time. But in our world they do, since The Clock is a clock, and you always know what time it is.

You know what time it is in the theater, though you may not know what time it is in the fiction. This is because in the sequence I saw today, some of the clocks were stopped. In a museum (perhaps the one that shooed people out at 4:45, but I don't think so), two characters look at a collage comprising pornographic magazine photos and photos of clocks, all showing the same time (the time The Clock is telling). Later a character comes in to find that his clock has been smashed. We can see when. It's the time on our watches. But clearly the clock has stopped long before. (And later there's another clip, Sound-and-the-Fury-ish, with a stopped watch and broken crystal, though I think maybe we see its owner breaking it with a hammer.) I wonder whether Marclay has the scene from Chinatown where J.J. picks up the crushed pocket watches he's placed under Mulwray's tires to see when he drove off. I wonder again - well, that's what the movie makes you do - whether Hitchcock winding the clock in Rear Window appears.

So what that made me realize is how much the movie is about clock- and watch-faces. How much, again, it's about movies themselves, and in particular watching movies, watching faces, looking at the photographed face. Hitchcock's joke in the Mt. Rushmore scenes of North By Northwest and Marclay's is about the fact that movies show faces on screen at unprecedented sizes: human and clock faces. (Well, Big Ben may be as big as any photographed clock, I guess.)

As Gloria Swanson put it in Sunset Boulevard: "We had faces!"

Showing posts with label Hitchcock. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Hitchcock. Show all posts

Saturday, November 12, 2011

Saturday, November 5, 2011

Names of Works: Names ("Turn of the Screw," for example)

What does Reservoir Dogs mean? Everyone knows: it's that movie that established Quentin Tarantino's reputation for gripping pulp violence, for a kind of pop pleasure in the interactions of large, primary-colored characters (figuratively as well as by way of their names) punctuated by violence, but where the violence isn't quite our central anxiety but part of the stakes in the story. Before you go see the movie, you assume you'll find out the significance of its title in the movie; afterwards you do know the significance: it's the perfect title for that Quentin Tarentino movie.

Yet, if you've seen it you know that there's no reservoir, no dog, no reference to their concatenation in the movie. Somehow the completely gripping story so fills your mind that when you've watching it, you don't notice that it skips the part where the meaning of the title gets explained. By the end, it just means that Quentin Tarantino movie, Reservoir Dogs.

Tarantino does this so effectively that we can see something really wonderful: an idiom aborning. The title has the same linguistic effect as an idiom: a piece of language that means the way words mean, but not by virtue of the combination that it comprises. The whole phrase easily dissolves into the flow of meaning, just like any other word. The hotly contested philosophical distinction between names and definite descriptions (cf. Russell, Kripke) comes undone in the case of what we could call the idiomatic name, the name that starts out looking like a description and then, after a while, doesn't.

I was thinking about this because I was thinking about The Turn of The Screw, and what the title means. Everyone knows, right? that Henry James novel, and also the sense of twist after possible twist. But why "turn of the screw"? The phrase appears in the novel twice, in that strange way that James has of treating bits of language as though they're common coin, even though they're not ("hang fire" being perhaps the most notorious). In the frame narrative, Douglas remarks about the ghost story that Griffin has just told,

Anyhow, the phrase is not an idiomatic one before James made it one. It does have an origin though: it's the title of a chapter in Bleak House ("A Turn of the Screw") in which Phil calls Joshua Smallweed "a screw and a wice in his actions." Thus the turn of the screw is the gradual increase of pressure, tightening what is already tight, turning a structure into nothing but itself, the way an idiom comes to mean only that untranslatable thing that the idiom captures so well.

This is essentially Blanchot's reading of the story. His great insight (greater even than what he was the first to remark: that the story is studiously and relentlessly ambiguous, not only about the real existence of the ghosts, but about whether it's ambiguous at all, an ambiguity which requires Miles to die) - his great insight is the importance of the fact that the governess is the narrator. What this means, he says, is not only that we don't know whether she's reliable, but that the subject of the story is its own narration, the narration of the fact that the narration is at issue. It's her story, which means that the content of the narrative is that it is a narrative: as with Proust it is, in the end, the story of the narrator as narrator.

Blanchot doesn't want to make this into some standard circular paradox of self-referentiality, any more than Proust does. He wants to see this collapsing of the difference between narrative and thing narrated as the pressure of narrative itself, increased sufficiently to squeeze out of narrative everything inessential, everything that isn't, finally, narrative pressure, so that the pressure of narrative is finally what it is: a pressure to be found only in the irreality of fiction because no fact of the matter, no truth, can come to resolve and relieve that pressure. The turn of the screw tightens the fiction to itself, makes of the work its own idiom or idiolect, a language you can learn but not one that you can translate, not in any literal, vulgar way, as we are warned from the start:

Yet, if you've seen it you know that there's no reservoir, no dog, no reference to their concatenation in the movie. Somehow the completely gripping story so fills your mind that when you've watching it, you don't notice that it skips the part where the meaning of the title gets explained. By the end, it just means that Quentin Tarantino movie, Reservoir Dogs.

Tarantino does this so effectively that we can see something really wonderful: an idiom aborning. The title has the same linguistic effect as an idiom: a piece of language that means the way words mean, but not by virtue of the combination that it comprises. The whole phrase easily dissolves into the flow of meaning, just like any other word. The hotly contested philosophical distinction between names and definite descriptions (cf. Russell, Kripke) comes undone in the case of what we could call the idiomatic name, the name that starts out looking like a description and then, after a while, doesn't.

I was thinking about this because I was thinking about The Turn of The Screw, and what the title means. Everyone knows, right? that Henry James novel, and also the sense of twist after possible twist. But why "turn of the screw"? The phrase appears in the novel twice, in that strange way that James has of treating bits of language as though they're common coin, even though they're not ("hang fire" being perhaps the most notorious). In the frame narrative, Douglas remarks about the ghost story that Griffin has just told,

"I quite agree—in regard to Griffin's ghost, or whatever it was—that its appearing first to the little boy, at so tender an age, adds a particular touch. But it's not the first occurrence of its charming kind that I know to have involved a child. If the child gives the effect another turn of the screw, what do you say to two children—?"And then later (though earlier in time), towards the end, the Governess describes yet once more the line she's had to pursue throughout her time at Bly:

"We say, of course," somebody exclaimed, "that they give two turns! Also that we want to hear about them."

Here at present I felt afresh—for I had felt it again and again—how my equilibrium depended on the success of my rigid will, the will to shut my eyes as tight as possible to the truth that what I had to deal with was, revoltingly, against nature. I could only get on at all by taking "nature" into my confidence and my account, by treating my monstrous ordeal as a push in a direction unusual, of course, and unpleasant, but demanding, after all, for a fair front, only another turn of the screw of ordinary human virtue.Sure, Douglas could have picked up the phrase from her, but that seems to be considering it too curiously, as though we're suddenly supposed to think back to the way she's influenced Douglas at this moment when she's praising the ordinary, confronting the ordinary against the ordeal. It feels more as though the phrase itself has become virtuously, valorously, ordinary, idiomatic, something that people do, in that wonderful offhanded praise (so like James) of "ordinary human virtue." What is a turn of the screw of ordinary human virtue? Even with just this context, these contexts, it means something like a tightening up of the apparatus, to make it more "rigid" (her word), more capable of resisting the stress or push it undergoes.

Anyhow, the phrase is not an idiomatic one before James made it one. It does have an origin though: it's the title of a chapter in Bleak House ("A Turn of the Screw") in which Phil calls Joshua Smallweed "a screw and a wice in his actions." Thus the turn of the screw is the gradual increase of pressure, tightening what is already tight, turning a structure into nothing but itself, the way an idiom comes to mean only that untranslatable thing that the idiom captures so well.

This is essentially Blanchot's reading of the story. His great insight (greater even than what he was the first to remark: that the story is studiously and relentlessly ambiguous, not only about the real existence of the ghosts, but about whether it's ambiguous at all, an ambiguity which requires Miles to die) - his great insight is the importance of the fact that the governess is the narrator. What this means, he says, is not only that we don't know whether she's reliable, but that the subject of the story is its own narration, the narration of the fact that the narration is at issue. It's her story, which means that the content of the narrative is that it is a narrative: as with Proust it is, in the end, the story of the narrator as narrator.

Blanchot doesn't want to make this into some standard circular paradox of self-referentiality, any more than Proust does. He wants to see this collapsing of the difference between narrative and thing narrated as the pressure of narrative itself, increased sufficiently to squeeze out of narrative everything inessential, everything that isn't, finally, narrative pressure, so that the pressure of narrative is finally what it is: a pressure to be found only in the irreality of fiction because no fact of the matter, no truth, can come to resolve and relieve that pressure. The turn of the screw tightens the fiction to itself, makes of the work its own idiom or idiolect, a language you can learn but not one that you can translate, not in any literal, vulgar way, as we are warned from the start:

Mrs. Griffin, however, expressed the need for a little more light. "Who was it she was in love with?"Waggish's recent post on MacGuffins put me in mind of this. For Hitchcock (and others) the MacGuffin is the mechanical narrative rabbit (hence the rabbit's foot of MI 3, perhaps), that the greyhounds of plot baying after it. But for Blanchot (and, if ironically, for Blumenberg) the MacGuffin isn't just (to change the metaphor) a catalyst, some reagent that gets things going and then withdraws. It's the work itself, the fact of narrative or of fiction, the thing that fiction wants to be able to tell: the significance of its own existence. And that's what it can't tell in any literal, vulgar way: if it could, its existence wouldn't be significant. If you chase the MacGuffin in James, or in Proust, or in Kafka (Blanchot compares the three of them) you may indeed go over to the world of parable. Is this in reality possible? Of course not. Only in parable. You have to learn another language and make its idioms your own, even if they don't translate into anything in your native tongue.

"The story will tell," I took upon myself to reply.

"Oh, I can't wait for the story!"

"The story won't tell," said Douglas; "not in any literal, vulgar way."

Saturday, July 30, 2011

Truth in Fiction - I: The State of Things

When I was in grad school, Wim Wenders came to talk about a movie of his, Der Stand der Dinge (the State of Things). I loved Wenders, and was glad that he was coming. After the movie I asked him what I thought was a very clever question about what was hidden under some stairs (iirc). He said he didn't know (which I knew he wouldn't), and I suggested that it was something from Johnny Guitar (Nicholas Ray is an extremely important precursor and mentor for Wenders). He looked at me as though I were batshit crazy, said no, it definitely wasn't that, and went on to the next questioner. I had imagined that he would get the important theoretical point that he was no more privileged as an interpreter of his own film than I was, and that what counted was the penetration of the reading (my reading), not the supposed authority of the reader (an authority that the author could pre-eminently claim). Literary theory, through its immense (and perennial) philosophical idealism had gone back round to treating fiction as though it were the representation of a true state of affairs, that anyone might be the first to see.

Truth in fiction didn't depend on what the fiction-maker meant. Its existence was independent of the fictionist's intention. Of course what made something true in a fiction was the interpretive aptness of the claim (like the notorious nineteenth century claim that Hamlet was a woman), such aptness measured by the insight it made possible. Insight into what? Well, into what was true in the fictional world. Such insight made, and could therefore find, the truth it claimed. Let's say it established truth. But that's what we do in the real world - we try to establish the truth.

Thus the only difference between the two - a difference which made possible the many-worlds interpretation of fictional interpretation - was the difference the article (the "the") suggests. In the real world we try to establish the truth, in fiction we try to establish truth.

Kendall Walton rightly argues that "truth in fiction," as D. K. Lewis called it, is a misnomer, since there's no requirement for logical consistency in a fictional world, on pain of deal-breaking incoherence. Deconstructive readings exploited the fact that most fictions are inconsistent, almost by their very nature, since fiction purports to know and to show things that cannot be known or showed: e.g. people alone with their thoughts, and the thoughts they're alone with (this particular inconsistency, rightly understood, is probably the one most central to deconstruction). Walton therefore prefers a technical use of the word "fictional": a proposition in a fiction would be called fictional if, as a stand-alone, it bore a relation to the fictional world it refers to analogous to the relation a true proposition bears to the real world. Fictional propositions don't have to appear in the fiction itself: they can be paraphrases or reasonable deductions or inductions from the propositions that appear there ("Hamlet dies at the end of the play"; and, probably, "Horatio lives on, with Fortinbras as King"). The reason for calling them fictional rather than "true in the fiction" is to suggest that not all their logical consequences are also true in the fiction. The dead Hermione's ghost appears to Antigonus... Hermione turns out not to have died. I think it's easier to say that both those statements are true in The Winter's Tale, rather than saying they're fictional in the play, but I've paused to rehearse Walton's argument because it brings out the difference between what I'm calling and will call fictional truth and the truth.

So we can tease out the implications of the difference the "the" makes by saying that our basic view of truth in the real world is Tractarian (i.e. conforms to the arguments of the early Wittgenstein): the consistency of the world will guarantee the consistency of the elementary propositions that picture it. Hence the world is all that is the case. Whereas our view of truth in fiction would be much more a coherence theory of truth: arguments about what happens in fiction require a reasonable amount of consistency among the various things that are true in that fiction, a consistency that makes it possible to handle the inconsistent parts that themselves contribute to the sense of coherence.

Still, at that time, in those days, the similarities seemed to us more important than the differences: the real world was coherent, and so was the fictional world. Ideal it may have been, but it shared with reality a presumption of completeness, and anything which made it complete could count as a live hypothesis about the fictional world, just as anything which explains away an apparent contradiction counts as a live hypothesis in the real world. In the real world, we are taught, we should always prefer the simplest possible account; in the fictional world we also used Occam's razor, but found that his straight edge didn't cut it and we had to plug in the electric one, which made possible all sorts of stylistic choices in the barbering of fictions hirsute with unexplained tufts of incident, character, or description. The simplest explanation is the best, but it's hard to define simplicity when in principle there's no reality check: it became a question of explaining all the fictional facts with a story supplementing the one we received. This of course was also what the New Testament did, and Midrash (where was Isaac after the Akedah?) and Kabbalah, and all manner of theologically inspired commentary and complement. Chandler might not know who killed Owen Taylor, but we could try to figure it out.

Now as the later Wittgenstein points out, there are an infinite number of sequences (of stories) that will explain any data (any fictional facts) that we are given. Since whatever sequence the author may have had in mind doesn't count more than any other, doesn't count more than the sequences readers may invent; since the logical inconsistencies, however trivial, show that even if we credit the author with authority over the meaning of her fiction, she nevertheless hasn't specified the whole sequence, item by item (any more than I have specified a whole sequence in my mind when I count 2, 4, 6, 8... that couldn't continue 1000, 1004, 1008, or - my favorite - 0, 1, 2, 720!, a number with 1,747 digits)* we deep readers felt entitled to our own penetrating, sequence producing fictional assertions about what happened offstage in the fictional world. Addition had no priority over quaddition, no matter what kind of real world type of pragmatism you inevitably evinced. There was no cash value to pragmatic truth in interpreting fiction - quite the reverse.

But to think this way is to lose the very thing that makes a fiction fiction, the universal literary genre we call fiction. It is to lose sight of the central law that the truth is what the author thinks it is (or what an authorial narrator, the last in the series, the narrator who has the author's full confidence, thinks it is). Narrating is one of the most basic forms of human interaction, of human sociability. "I've got a story": words which promise pleasure to both teller and told. The pleasures are different: the teller takes pleasure in promulgating, the listener or reader in learning (as Aristotle pointed out already in the Poetics). No stories without tellers is the moral of this one.

A moral more complicated than it might seem, it plays out differently according to the kind of story being told. A quick taxonomy would distinguish between true stories and fiction, but we have to add a third phylum: anonymous stories whose origin is lost in the mists of time (folk tales, myths, legends, etc.). When someone is telling a true story, we're entitled (rude though it might be) to second-guess her interpretations. Some people always do. I tell a story about a jerk cutting me off on the 405, but my skeptical listener suggests I might be in the wrong. He thinks the truth (the single truth) might be different from what my story is suggesting, that there is a fact of the matter and I'm misrepresenting it. This is true of third person stories as well: I say that Babe Ruth called his shot; she says, No, he was stretching prior to batting, and it just looked like he was pointing.

My skeptical chum doesn't have the same right to say that about a fictional narrative I originate. I get to say what my characters have known, have planned, have anticipated, have done. If Wenders denies that there's something under the stairs, if his denial is serious, his skepticism genuine, no one is entitled to gainsay him. It doesn't matter if the author is dead (you know, literally, biologically, dead). Our sense of her is that what she thought happened happened. We may not know what she thought happened, but we're still appealing to that category. Who killed Edwin Drood? We'll never know, but Dickens sure did.

The third phylum is the tale, which intersects the other two, and with their common ground. If you've heard a story, I can think you've heard it wrong, or that there's a way to tweak it to make it better. It's fiction, but it's like the truth in the sense that it's public property. No one has exclusive rights to it. Here the teller is more or less like a literary critic, or an actor: an interpreter of a story that comes from elsewhere. But her interpretation also gives her the authority that a witness has when it comes to telling true stories: she has a somewhat privileged, but defeasible relation to a public truth. More defeasible than an actual witnesses would have, since once I know the story I am as entitled to tell it in the way I think best as she was. There are no rules against hearsay in this phylum: indeed hearsay is obligatory, even or especially with all the hopeful mutation hearsay can introduce.

My interest, though, is in the authority the teller has over the tale, an authority most marked in the second phylum, the one where the fiction has an indentifiable author. Here the strangeness of fiction - that we care about what we know isn't true - and the importance of the teller are both at their maxima. And yet, the author is still governed by some coherence-producing restraints. 0, 1, 2, 720! will rarely do (though perhaps that's David Lynch's speciality). Chandler may not know who killed Owen Taylor, but he would have wanted to know, would have decided and established who did, had he realized that hadn't known. He doesn't know, and now there's nothing to know. There is something to know about who killed Edwin Drood, but we never will know it: ignorabimus.

That constraint, like poetic form, can be a goad and a spur to the fictionist. Lewis Carroll has to come up with the answer to random riddles he's posed - and he does (How is a raven like a writing desk?) The whole movie in the can, and being shown to test audiences, Hitchcock decides (the audience has a hand in this, as it should) that Cary Grant had better be innocent. Hitchcock comes up with an ingenious ending explaining away all the Suspicions. Javier Marías never returns to revise a page once he's done with it: he has to cope with the fictional truth of the fictional past, to explain the drop of blood or the behavior of young Pérez Nuix. Writers had to do this all the time in the age of serials: TV writers still do, though it's more interesting as in the case of Marías or (I think) Helen DeWitt when you have produced your own constraints. (DeWitt is endlessly inventive and then endlessly attentive to the implications and consequences of her inventions. DFW is sometimes like that too.)

Truth in fiction: there is a fact of the matter, but that means there are privileged relations to the facts, authoritative perspectives, certified fact-finders. (Otherwise no one would need to listen - everyone would already know that the tale referred to the fictional just as Frege says that true propositions refer to the true.) Even when we tweak anonymous tales, we usually think we're getting back to what they must originally have been, or at least we present them as the more authentic versions. (Or else we transmute them into something frankly our own, become their announced authors, even if we're anonymous: "by the author of Waverly, &c.") The risibly clever "fact" I offered Wenders showed that I got right that fiction trades in truths; what I got wrong though, was the way that such truth is in principle only available through the teller and her actions as a teller. We all trust our own judgment, and all human communication is a comparison of divergent judgment (no matter how small the divergence) - otherwise it's not communication.

But then how can we compare our own judgment about the world she has invented with that of the fictionist? And how can we know the truths she's left to our own inference - what prevents us from inferring the world we want to infer when we have a chance?

--------------

*In case you're curious, here are all 1,747 digits of the fourth number in the sequence whose first three numbers are 0, 1, 2 written out:

260,121,894,356,579,510,020,490,322,708,104,361,119,152,187,501,694,578,572,754,183,785,083,563,115,694,738,224,067,857,795,813,045,708,261,992,057,589,224,725,953,664,156,516,205,201,587,379,198,458,774,083,252,910,524,469,038,881,188,412,376,434,119,195,104,550,534,665,861,624,327,194,019,711,390,984,553,672,727,853,709,934,562,985,558,671,936,977,407,000,370,043,078,375,899,742,067,678,401,696,720,784,280,629,229,032,107,161,669,867,260,548,988,445,514,257,193,985,499,448,939,594,496,064,045,132,362,140,265,986,193,073,249,369,770,477,606,067,680,670,176,491,669,403,034,819,961,881,455,625,195,592,566,918,830,825,514,942,947,596,537,274,845,624,628,824,234,526,597,789,737,740,896,466,553,992,435,928,786,212,515,967,483,220,976,029,505,696,699,927,284,670,563,747,137,533,019,248,313,587,076,125,412,683,415,860,129,447,566,011,455,420,749,589,952,563,543,068,288,634,631,084,965,650,682,771,552,996,256,790,845,235,702,552,186,222,358,130,016,700,834,523,443,236,821,935,793,184,701,956,510,729,781,804,354,173,890,560,727,428,048,583,995,919,729,021,726,612,291,298,420,516,067,579,036,232,337,699,453,964,191,475,175,567,557,695,392,233,803,056,825,308,599,977,441,675,784,352,815,913,461,340,394,604,901,269,542,028,838,347,101,363,733,824,484,506,660,093,348,484,440,711,931,292,537,694,657,354,337,375,724,772,230,181,534,032,647,177,531,984,537,341,478,674,327,048,457,983,786,618,703,257,405,938,924,215,709,695,994,630,557,521,063,203,263,493,209,220,738,320,923,356,309,923,267,504,401,701,760,572,026,010,829,288,042,335,606,643,089,888,710,297,380,797,578,013,056,049,576,342,838,683,057,190,662,205,291,174,822,510,536,697,756,603,029,574,043,387,983,471,518,552,602,805,333,866,357,139,101,046,336,419,769,097,397,432,285,994,219,837,046,979,109,956,303,389,604,675,889,865,795,711,176,566,670,039,156,748,153,115,943,980,043,625,399,399,731,203,066,490,601,325,311,304,719,028,898,491,856,203,766,669,164,468,791,125,249,193,754,425,845,895,000,311,561,682,974,304,641,142,538,074,897,281,723,375,955,380,661,719,801,404,677,935,614,793,635,266,265,683,339,509,760,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000

Truth in fiction didn't depend on what the fiction-maker meant. Its existence was independent of the fictionist's intention. Of course what made something true in a fiction was the interpretive aptness of the claim (like the notorious nineteenth century claim that Hamlet was a woman), such aptness measured by the insight it made possible. Insight into what? Well, into what was true in the fictional world. Such insight made, and could therefore find, the truth it claimed. Let's say it established truth. But that's what we do in the real world - we try to establish the truth.

Thus the only difference between the two - a difference which made possible the many-worlds interpretation of fictional interpretation - was the difference the article (the "the") suggests. In the real world we try to establish the truth, in fiction we try to establish truth.

Kendall Walton rightly argues that "truth in fiction," as D. K. Lewis called it, is a misnomer, since there's no requirement for logical consistency in a fictional world, on pain of deal-breaking incoherence. Deconstructive readings exploited the fact that most fictions are inconsistent, almost by their very nature, since fiction purports to know and to show things that cannot be known or showed: e.g. people alone with their thoughts, and the thoughts they're alone with (this particular inconsistency, rightly understood, is probably the one most central to deconstruction). Walton therefore prefers a technical use of the word "fictional": a proposition in a fiction would be called fictional if, as a stand-alone, it bore a relation to the fictional world it refers to analogous to the relation a true proposition bears to the real world. Fictional propositions don't have to appear in the fiction itself: they can be paraphrases or reasonable deductions or inductions from the propositions that appear there ("Hamlet dies at the end of the play"; and, probably, "Horatio lives on, with Fortinbras as King"). The reason for calling them fictional rather than "true in the fiction" is to suggest that not all their logical consequences are also true in the fiction. The dead Hermione's ghost appears to Antigonus... Hermione turns out not to have died. I think it's easier to say that both those statements are true in The Winter's Tale, rather than saying they're fictional in the play, but I've paused to rehearse Walton's argument because it brings out the difference between what I'm calling and will call fictional truth and the truth.

So we can tease out the implications of the difference the "the" makes by saying that our basic view of truth in the real world is Tractarian (i.e. conforms to the arguments of the early Wittgenstein): the consistency of the world will guarantee the consistency of the elementary propositions that picture it. Hence the world is all that is the case. Whereas our view of truth in fiction would be much more a coherence theory of truth: arguments about what happens in fiction require a reasonable amount of consistency among the various things that are true in that fiction, a consistency that makes it possible to handle the inconsistent parts that themselves contribute to the sense of coherence.

Still, at that time, in those days, the similarities seemed to us more important than the differences: the real world was coherent, and so was the fictional world. Ideal it may have been, but it shared with reality a presumption of completeness, and anything which made it complete could count as a live hypothesis about the fictional world, just as anything which explains away an apparent contradiction counts as a live hypothesis in the real world. In the real world, we are taught, we should always prefer the simplest possible account; in the fictional world we also used Occam's razor, but found that his straight edge didn't cut it and we had to plug in the electric one, which made possible all sorts of stylistic choices in the barbering of fictions hirsute with unexplained tufts of incident, character, or description. The simplest explanation is the best, but it's hard to define simplicity when in principle there's no reality check: it became a question of explaining all the fictional facts with a story supplementing the one we received. This of course was also what the New Testament did, and Midrash (where was Isaac after the Akedah?) and Kabbalah, and all manner of theologically inspired commentary and complement. Chandler might not know who killed Owen Taylor, but we could try to figure it out.

Now as the later Wittgenstein points out, there are an infinite number of sequences (of stories) that will explain any data (any fictional facts) that we are given. Since whatever sequence the author may have had in mind doesn't count more than any other, doesn't count more than the sequences readers may invent; since the logical inconsistencies, however trivial, show that even if we credit the author with authority over the meaning of her fiction, she nevertheless hasn't specified the whole sequence, item by item (any more than I have specified a whole sequence in my mind when I count 2, 4, 6, 8... that couldn't continue 1000, 1004, 1008, or - my favorite - 0, 1, 2, 720!, a number with 1,747 digits)* we deep readers felt entitled to our own penetrating, sequence producing fictional assertions about what happened offstage in the fictional world. Addition had no priority over quaddition, no matter what kind of real world type of pragmatism you inevitably evinced. There was no cash value to pragmatic truth in interpreting fiction - quite the reverse.

But to think this way is to lose the very thing that makes a fiction fiction, the universal literary genre we call fiction. It is to lose sight of the central law that the truth is what the author thinks it is (or what an authorial narrator, the last in the series, the narrator who has the author's full confidence, thinks it is). Narrating is one of the most basic forms of human interaction, of human sociability. "I've got a story": words which promise pleasure to both teller and told. The pleasures are different: the teller takes pleasure in promulgating, the listener or reader in learning (as Aristotle pointed out already in the Poetics). No stories without tellers is the moral of this one.

A moral more complicated than it might seem, it plays out differently according to the kind of story being told. A quick taxonomy would distinguish between true stories and fiction, but we have to add a third phylum: anonymous stories whose origin is lost in the mists of time (folk tales, myths, legends, etc.). When someone is telling a true story, we're entitled (rude though it might be) to second-guess her interpretations. Some people always do. I tell a story about a jerk cutting me off on the 405, but my skeptical listener suggests I might be in the wrong. He thinks the truth (the single truth) might be different from what my story is suggesting, that there is a fact of the matter and I'm misrepresenting it. This is true of third person stories as well: I say that Babe Ruth called his shot; she says, No, he was stretching prior to batting, and it just looked like he was pointing.

My skeptical chum doesn't have the same right to say that about a fictional narrative I originate. I get to say what my characters have known, have planned, have anticipated, have done. If Wenders denies that there's something under the stairs, if his denial is serious, his skepticism genuine, no one is entitled to gainsay him. It doesn't matter if the author is dead (you know, literally, biologically, dead). Our sense of her is that what she thought happened happened. We may not know what she thought happened, but we're still appealing to that category. Who killed Edwin Drood? We'll never know, but Dickens sure did.

The third phylum is the tale, which intersects the other two, and with their common ground. If you've heard a story, I can think you've heard it wrong, or that there's a way to tweak it to make it better. It's fiction, but it's like the truth in the sense that it's public property. No one has exclusive rights to it. Here the teller is more or less like a literary critic, or an actor: an interpreter of a story that comes from elsewhere. But her interpretation also gives her the authority that a witness has when it comes to telling true stories: she has a somewhat privileged, but defeasible relation to a public truth. More defeasible than an actual witnesses would have, since once I know the story I am as entitled to tell it in the way I think best as she was. There are no rules against hearsay in this phylum: indeed hearsay is obligatory, even or especially with all the hopeful mutation hearsay can introduce.

My interest, though, is in the authority the teller has over the tale, an authority most marked in the second phylum, the one where the fiction has an indentifiable author. Here the strangeness of fiction - that we care about what we know isn't true - and the importance of the teller are both at their maxima. And yet, the author is still governed by some coherence-producing restraints. 0, 1, 2, 720! will rarely do (though perhaps that's David Lynch's speciality). Chandler may not know who killed Owen Taylor, but he would have wanted to know, would have decided and established who did, had he realized that hadn't known. He doesn't know, and now there's nothing to know. There is something to know about who killed Edwin Drood, but we never will know it: ignorabimus.

That constraint, like poetic form, can be a goad and a spur to the fictionist. Lewis Carroll has to come up with the answer to random riddles he's posed - and he does (How is a raven like a writing desk?) The whole movie in the can, and being shown to test audiences, Hitchcock decides (the audience has a hand in this, as it should) that Cary Grant had better be innocent. Hitchcock comes up with an ingenious ending explaining away all the Suspicions. Javier Marías never returns to revise a page once he's done with it: he has to cope with the fictional truth of the fictional past, to explain the drop of blood or the behavior of young Pérez Nuix. Writers had to do this all the time in the age of serials: TV writers still do, though it's more interesting as in the case of Marías or (I think) Helen DeWitt when you have produced your own constraints. (DeWitt is endlessly inventive and then endlessly attentive to the implications and consequences of her inventions. DFW is sometimes like that too.)

Truth in fiction: there is a fact of the matter, but that means there are privileged relations to the facts, authoritative perspectives, certified fact-finders. (Otherwise no one would need to listen - everyone would already know that the tale referred to the fictional just as Frege says that true propositions refer to the true.) Even when we tweak anonymous tales, we usually think we're getting back to what they must originally have been, or at least we present them as the more authentic versions. (Or else we transmute them into something frankly our own, become their announced authors, even if we're anonymous: "by the author of Waverly, &c.") The risibly clever "fact" I offered Wenders showed that I got right that fiction trades in truths; what I got wrong though, was the way that such truth is in principle only available through the teller and her actions as a teller. We all trust our own judgment, and all human communication is a comparison of divergent judgment (no matter how small the divergence) - otherwise it's not communication.

But then how can we compare our own judgment about the world she has invented with that of the fictionist? And how can we know the truths she's left to our own inference - what prevents us from inferring the world we want to infer when we have a chance?

--------------

*In case you're curious, here are all 1,747 digits of the fourth number in the sequence whose first three numbers are 0, 1, 2 written out:

260,121,894,356,579,510,020,490,322,708,104,361,119,152,187,501,694,578,572,754,183,785,083,563,115,694,738,224,067,857,795,813,045,708,261,992,057,589,224,725,953,664,156,516,205,201,587,379,198,458,774,083,252,910,524,469,038,881,188,412,376,434,119,195,104,550,534,665,861,624,327,194,019,711,390,984,553,672,727,853,709,934,562,985,558,671,936,977,407,000,370,043,078,375,899,742,067,678,401,696,720,784,280,629,229,032,107,161,669,867,260,548,988,445,514,257,193,985,499,448,939,594,496,064,045,132,362,140,265,986,193,073,249,369,770,477,606,067,680,670,176,491,669,403,034,819,961,881,455,625,195,592,566,918,830,825,514,942,947,596,537,274,845,624,628,824,234,526,597,789,737,740,896,466,553,992,435,928,786,212,515,967,483,220,976,029,505,696,699,927,284,670,563,747,137,533,019,248,313,587,076,125,412,683,415,860,129,447,566,011,455,420,749,589,952,563,543,068,288,634,631,084,965,650,682,771,552,996,256,790,845,235,702,552,186,222,358,130,016,700,834,523,443,236,821,935,793,184,701,956,510,729,781,804,354,173,890,560,727,428,048,583,995,919,729,021,726,612,291,298,420,516,067,579,036,232,337,699,453,964,191,475,175,567,557,695,392,233,803,056,825,308,599,977,441,675,784,352,815,913,461,340,394,604,901,269,542,028,838,347,101,363,733,824,484,506,660,093,348,484,440,711,931,292,537,694,657,354,337,375,724,772,230,181,534,032,647,177,531,984,537,341,478,674,327,048,457,983,786,618,703,257,405,938,924,215,709,695,994,630,557,521,063,203,263,493,209,220,738,320,923,356,309,923,267,504,401,701,760,572,026,010,829,288,042,335,606,643,089,888,710,297,380,797,578,013,056,049,576,342,838,683,057,190,662,205,291,174,822,510,536,697,756,603,029,574,043,387,983,471,518,552,602,805,333,866,357,139,101,046,336,419,769,097,397,432,285,994,219,837,046,979,109,956,303,389,604,675,889,865,795,711,176,566,670,039,156,748,153,115,943,980,043,625,399,399,731,203,066,490,601,325,311,304,719,028,898,491,856,203,766,669,164,468,791,125,249,193,754,425,845,895,000,311,561,682,974,304,641,142,538,074,897,281,723,375,955,380,661,719,801,404,677,935,614,793,635,266,265,683,339,509,760,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000

Labels:

Aristotle,

D.K. Lewis,

fiction,

Frege,

Helen DeWitt,

Hitchcock,

hopeful monster,

Javier Marías,

Kendall Walton,

Kripke,

Nicholas Ray,

Occam's razor,

quaddition,

Raymond Chandler,

truth,

Wim Wenders,

Wittgenstein

Friday, June 17, 2011

Film, will, and the paradox of imperceptible differences; or Body English

There's an interesting philosophical problem about the nature of imperceptiblity, related to the problem of sorites (at some point a baby stops being a baby: when?). I thought I'd post my ideas about this, partly prompted by a recent and somewhat cantankerous essay by the great David Bordwell, with which I agree with in part and disagree in part.

Consider four photos of the hands of a watch, taken at, say, 1/24th of a second apart. Put them in front of someone and ask her which one was taken first:

I didn't manage to crop these quite the same (that's an issue we'll come back to: changes in the perceiver's or recorder's perspective), but just look at the hands of the watch. These shots were taken within about a quarter of a second of each other, so on average they're about 1/12th of a second apart - twice the 1/24th of a second we're hypothesizing. I present them here randomly (I followed the order of the last four digits of my Frequent Flyer number). Can you tell the order they were taken? (Answer: The order is 4,1, 2, 3 - I think you can just make the sequence out if you squint, but if not, highlight all and you'll be able to.)

At some point, though, you'll be able to see that the hands have moved, that it's now (more or less) 9:03 and not 9:01.

So the paradox of imperceptibility is this. Let's say call p the minimal distance that the hand of a normal-sized watch has to move for us to perceive -- by eyeballing two different life-sized photos -- that it has moved. The order of magnitude for p here is probably something like twelve minutes of arc or so (for the big hand that would be about two temporal seconds, for the little hand two temporal minutes). At any rate, the photos above don't show anything like a difference of magnitude p. We're talking about a total of a quarter of a second here, which is why there's no way you can tell the order by looking. (Funes could, I suppose.)

Now consider two photos identical except in the second of them the minute hand is at a distance of 1.6p from the first; i.e. 3.2 seconds have elapsed between the two photos. Just looking you can tell the difference! (Remember that's what p means: the distance greater than which you can see the difference.)

Now imagine interpolating a third photo, which shows the minute hand at a distance of .8p past the first photo, and accordingly at a distance of .8p before the second photo; i.e. this third photo was taken 1.6 seconds after the first, and 1.6 seconds before the second. In other words, let's assume we're looking at a sequence of three photos, taken 1.6 seconds apart.

So here's what exercises the new Zenonians. You can't tell the difference between the first and the second photo (we've stipulated that the minimal difference you can tell is p, the distance it takes the minute hand two seconds to cover), nor can you tell the difference between the second and the third, but you can tell the difference between the first and the third. So you perceive no difference between the first and the second, and no difference between the second and the third, and yet, somehow, somewhere, you must perceive some difference or you wouldn't perceive a difference between the first and the third. (There's a strange failure of the transitivity we expect here.)

To see how this is true, consider ordering the photos to present them to someone else. Since there's no perceptible difference between the first and the second, you should be able to switch them around, and no one will be the wiser. But if you do that there'll be a perceptible difference between the new second and the third. You can't see the difference between one and two, so their order seems not to matter; but switch them and you can now see a difference between two and three, so their order did matter.

That's the problem. People have tried to solve it with vague appeals to threshold differences, but the new Zenonians point out that this is just to rename it, since the whole point is to ask what makes something exceed the threshold of perceptibility. P defines that threshold, but we've already said that. An appeal to a threshold only changes the vocabulary.

Here's my solution. Look at any two indistinguishable photos whatever: even at the same photo twice. There'll always be a perceptible difference between the two. Your head will have moved slightly, the light will have changed, your eyes will have performed some micro-saccades, the beat of your pulse will cause the image to shudder, your breath will inspire it to fitful and inconstant motion. But you'll read the two different retinal images as identical, because part of visual processing consists in abstracting from the incessant flux of experience by fixing on what J.J. Gibson called invariants. The brain uses these invariants (edge ratios, color ratios, etc.) to calculate what's changing in the world vs. what's changing in your perceptual apparatus.

Accordingly, we're always testing the origin of the perceptual changes that occur every moment. This is an argument that Kant was the first to make, as he analyzed the nature of our capacity to distinguish between seeing a boat move downstream and a house standing still. Both visual experiences come to us through the incessant flux of appearance: I see a window, a door, a lintel, an eave, in any order; or I see a prow, a stern, a sail, an oar. But I am proprioceptively aware of the fact that the flux in my view of the house comes from movements I am myself making, that originate in my own will. (William James argues that the difference between proprioceptive awareness of unforced change and the experience of willing is essentially nonexistent.) The flux in my perception of the boat isn't assignable only to my own will.

At some fairly automatic level our brains proprioceptively track our microsaccadic eye-movements and assign the origin of the flux we see in an unmoving object to our own movements. At some point we'll begin to wonder whether, and at a later point decide that, we're seeing more flux than we can explain through our automatic proprioceptive guidance systems.

Vertigo provides an obvious example of this fact. If we mess with the vestibular system (by spinning around, by drinking), we lose a very important proprioceptive clue as to the attitude of our heads. Now we're reeling and seem to stand upon the ceiling: the room is still but we think it's moving. Closing your eyes helps because you stop seeing the motion that they're making, stop projecting it into the world.

So no case of motion may be absolutely assigned to one domain or the other, to the world or to the seeing soul. But usually we start with a very good guess as to where the motion is. This also explains a feature of vertigo: the way we cast our eyes everywhere trying to find something that will stay still to orient ourselves by.

Imperceptibile motion, then, is motion whose perception is swamped by the normal flux of appearance.

Consider the converse idea: that of imperceptible stillness. I feel as though I've been waiting for this class to end forever. Has the clock stopped or am I so bored that every minute seems five? I keep looking at the clock, and after a while, I start realizing that it's broken. It's frozen but I thought it was moving. I decide that it's frozen in several stages: I wonder, I concentrate, I observe closely, I wait a little longer, and after a while I make a judgment: it's not fucking moving.

Likewise imperceptible motion occurs when I think something is still (when my automatic visual processing takes something as still), but then after a while start wondering if it really is still. I am not sure the flux derives only from myself. I start testing the hypothesis that the minute hand itself has moved. That hypothesis is easier to test the more it moves. Nothing makes it certain that the motion comes from the world, and not from me, but I become more and more confident that certain intervals are more likely to be due to a change in the object than to a change in my own perspective.

Body English -- you know, as with Carlton Fisk's stay-fair home run -- provides a vivid example of what I mean: you move your own body to some extreme angle to get a preferred perspective on the ball. Of course you know that this doesn't affect its trajectory, but you can fool or try to fool your perceptual apparatus into thinking that the change you see is a change in what you're seeing, not in yourself.

The fact that perception always involves the will, gyroscopically orienting the telemetry of the senses, means you can dally with false surmise by flooding the proprioceptive stabilizers of perception a little bit. We can pick the locks of perception (by spinning around or crouching and cocking our heads or whatever) and so perceive a little more wishfully than accurately, when we really want to. This shouldn't be surprising: it's the will after all that's being engaged. We move in certain ways because we want certain things to happen, and our motion sometimes affects the world (and so our perception of it), sometimes just our perception of the world. The fact that we engage so much in body English shows that the frontier between what our brains think comes from outside and what they think comes from inside is porous and vague. The two types of willing are continuous, no doubt because all perception requires the same sort of experimental assessment of how (or whether) it's going as action does. A single way of doing that experimental assessment governs both cases, and can turn one into the other.

Film depends on this fact about impercetible motion, in more ways than one. Two frames, 1/24th of a second apart, will often be indistinguishable. (Not to Fred Astaire, apparently, who'd fiddle with single sprockets in his movies, to get the beat exactly right. I believe the technology was eight sprockets per frame when he made his great movies, so that would mean he was able to perceive differences at about 1/200th of a second. But no one had more motor control, and therefore more fineness of proprioception than Astaire.) But of course over eight frames you can see any perceivable motion - that's a third of a second. So when we watch a movie, we're brought to judge motion as imperceptible differences - differences we would ascribe to the noise of the perceptual system - make themselves felt as perceptible.

But that means that we're constantly judging what we're seeing, through the engagement of our will. In well-edited films, the films themselves will, through what we could call cinematic occasionalism, conform to our own acts of willing. Someone looks right. We want to see what they're looking at. The camera or the editor obliges. In classic Hollywood film the audience almost always feels in control of the camera. (The times that we don't, at least in a good movie, are generally the places where we feel the pleasure of being played: think of any Hitchcock film.) Film, and classic Hollywood film especially, exploits our negotiations with our own perceptual flux, and engages our will in ways that minister to narrative desire, to the body English that makes us try to see things as acting the way we want them to act.

I think that what we have here is a natural analogue to Newcomb's Problem. By choosing our perceptions right, we may be able to get what we want. If that's how the psychology of narrative works (through the general phenomenon that I call non-causal bargaining), then on every scale, from 1/24th of a second to two or more hours, our relation to film keeps our occasionalist testing of what we see highly sensitized and engaged. This would make film a particularly apt medium for narrative engagement (probably just about as apt as language, where I think we do a similar sort of testing).

Obviously I wouldn't confine this to Hollywood movies: Chatal Akerman's Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles is a case in point: we watch Jeanne over three days and start noting the tiny differences in what she's doing. Are they artifacts of film making or are they action? That's the question that animates our perception of the movie.

The perception of all action requires our involvement, and the more our involvement is fictional or factitious, even on the level of the most basic perception, the more it enmeshes our willing and our wishing, our desire and our engagement in non-causal bargaining.

Consider four photos of the hands of a watch, taken at, say, 1/24th of a second apart. Put them in front of someone and ask her which one was taken first:

I didn't manage to crop these quite the same (that's an issue we'll come back to: changes in the perceiver's or recorder's perspective), but just look at the hands of the watch. These shots were taken within about a quarter of a second of each other, so on average they're about 1/12th of a second apart - twice the 1/24th of a second we're hypothesizing. I present them here randomly (I followed the order of the last four digits of my Frequent Flyer number). Can you tell the order they were taken? (Answer: The order is 4,1, 2, 3 - I think you can just make the sequence out if you squint, but if not, highlight all and you'll be able to.)

At some point, though, you'll be able to see that the hands have moved, that it's now (more or less) 9:03 and not 9:01.

So the paradox of imperceptibility is this. Let's say call p the minimal distance that the hand of a normal-sized watch has to move for us to perceive -- by eyeballing two different life-sized photos -- that it has moved. The order of magnitude for p here is probably something like twelve minutes of arc or so (for the big hand that would be about two temporal seconds, for the little hand two temporal minutes). At any rate, the photos above don't show anything like a difference of magnitude p. We're talking about a total of a quarter of a second here, which is why there's no way you can tell the order by looking. (Funes could, I suppose.)

Now consider two photos identical except in the second of them the minute hand is at a distance of 1.6p from the first; i.e. 3.2 seconds have elapsed between the two photos. Just looking you can tell the difference! (Remember that's what p means: the distance greater than which you can see the difference.)

Now imagine interpolating a third photo, which shows the minute hand at a distance of .8p past the first photo, and accordingly at a distance of .8p before the second photo; i.e. this third photo was taken 1.6 seconds after the first, and 1.6 seconds before the second. In other words, let's assume we're looking at a sequence of three photos, taken 1.6 seconds apart.

So here's what exercises the new Zenonians. You can't tell the difference between the first and the second photo (we've stipulated that the minimal difference you can tell is p, the distance it takes the minute hand two seconds to cover), nor can you tell the difference between the second and the third, but you can tell the difference between the first and the third. So you perceive no difference between the first and the second, and no difference between the second and the third, and yet, somehow, somewhere, you must perceive some difference or you wouldn't perceive a difference between the first and the third. (There's a strange failure of the transitivity we expect here.)

To see how this is true, consider ordering the photos to present them to someone else. Since there's no perceptible difference between the first and the second, you should be able to switch them around, and no one will be the wiser. But if you do that there'll be a perceptible difference between the new second and the third. You can't see the difference between one and two, so their order seems not to matter; but switch them and you can now see a difference between two and three, so their order did matter.

That's the problem. People have tried to solve it with vague appeals to threshold differences, but the new Zenonians point out that this is just to rename it, since the whole point is to ask what makes something exceed the threshold of perceptibility. P defines that threshold, but we've already said that. An appeal to a threshold only changes the vocabulary.

Here's my solution. Look at any two indistinguishable photos whatever: even at the same photo twice. There'll always be a perceptible difference between the two. Your head will have moved slightly, the light will have changed, your eyes will have performed some micro-saccades, the beat of your pulse will cause the image to shudder, your breath will inspire it to fitful and inconstant motion. But you'll read the two different retinal images as identical, because part of visual processing consists in abstracting from the incessant flux of experience by fixing on what J.J. Gibson called invariants. The brain uses these invariants (edge ratios, color ratios, etc.) to calculate what's changing in the world vs. what's changing in your perceptual apparatus.

Accordingly, we're always testing the origin of the perceptual changes that occur every moment. This is an argument that Kant was the first to make, as he analyzed the nature of our capacity to distinguish between seeing a boat move downstream and a house standing still. Both visual experiences come to us through the incessant flux of appearance: I see a window, a door, a lintel, an eave, in any order; or I see a prow, a stern, a sail, an oar. But I am proprioceptively aware of the fact that the flux in my view of the house comes from movements I am myself making, that originate in my own will. (William James argues that the difference between proprioceptive awareness of unforced change and the experience of willing is essentially nonexistent.) The flux in my perception of the boat isn't assignable only to my own will.

At some fairly automatic level our brains proprioceptively track our microsaccadic eye-movements and assign the origin of the flux we see in an unmoving object to our own movements. At some point we'll begin to wonder whether, and at a later point decide that, we're seeing more flux than we can explain through our automatic proprioceptive guidance systems.

Vertigo provides an obvious example of this fact. If we mess with the vestibular system (by spinning around, by drinking), we lose a very important proprioceptive clue as to the attitude of our heads. Now we're reeling and seem to stand upon the ceiling: the room is still but we think it's moving. Closing your eyes helps because you stop seeing the motion that they're making, stop projecting it into the world.

So no case of motion may be absolutely assigned to one domain or the other, to the world or to the seeing soul. But usually we start with a very good guess as to where the motion is. This also explains a feature of vertigo: the way we cast our eyes everywhere trying to find something that will stay still to orient ourselves by.

Imperceptibile motion, then, is motion whose perception is swamped by the normal flux of appearance.

Consider the converse idea: that of imperceptible stillness. I feel as though I've been waiting for this class to end forever. Has the clock stopped or am I so bored that every minute seems five? I keep looking at the clock, and after a while, I start realizing that it's broken. It's frozen but I thought it was moving. I decide that it's frozen in several stages: I wonder, I concentrate, I observe closely, I wait a little longer, and after a while I make a judgment: it's not fucking moving.

Likewise imperceptible motion occurs when I think something is still (when my automatic visual processing takes something as still), but then after a while start wondering if it really is still. I am not sure the flux derives only from myself. I start testing the hypothesis that the minute hand itself has moved. That hypothesis is easier to test the more it moves. Nothing makes it certain that the motion comes from the world, and not from me, but I become more and more confident that certain intervals are more likely to be due to a change in the object than to a change in my own perspective.

Body English -- you know, as with Carlton Fisk's stay-fair home run -- provides a vivid example of what I mean: you move your own body to some extreme angle to get a preferred perspective on the ball. Of course you know that this doesn't affect its trajectory, but you can fool or try to fool your perceptual apparatus into thinking that the change you see is a change in what you're seeing, not in yourself.

The fact that perception always involves the will, gyroscopically orienting the telemetry of the senses, means you can dally with false surmise by flooding the proprioceptive stabilizers of perception a little bit. We can pick the locks of perception (by spinning around or crouching and cocking our heads or whatever) and so perceive a little more wishfully than accurately, when we really want to. This shouldn't be surprising: it's the will after all that's being engaged. We move in certain ways because we want certain things to happen, and our motion sometimes affects the world (and so our perception of it), sometimes just our perception of the world. The fact that we engage so much in body English shows that the frontier between what our brains think comes from outside and what they think comes from inside is porous and vague. The two types of willing are continuous, no doubt because all perception requires the same sort of experimental assessment of how (or whether) it's going as action does. A single way of doing that experimental assessment governs both cases, and can turn one into the other.

Film depends on this fact about impercetible motion, in more ways than one. Two frames, 1/24th of a second apart, will often be indistinguishable. (Not to Fred Astaire, apparently, who'd fiddle with single sprockets in his movies, to get the beat exactly right. I believe the technology was eight sprockets per frame when he made his great movies, so that would mean he was able to perceive differences at about 1/200th of a second. But no one had more motor control, and therefore more fineness of proprioception than Astaire.) But of course over eight frames you can see any perceivable motion - that's a third of a second. So when we watch a movie, we're brought to judge motion as imperceptible differences - differences we would ascribe to the noise of the perceptual system - make themselves felt as perceptible.

But that means that we're constantly judging what we're seeing, through the engagement of our will. In well-edited films, the films themselves will, through what we could call cinematic occasionalism, conform to our own acts of willing. Someone looks right. We want to see what they're looking at. The camera or the editor obliges. In classic Hollywood film the audience almost always feels in control of the camera. (The times that we don't, at least in a good movie, are generally the places where we feel the pleasure of being played: think of any Hitchcock film.) Film, and classic Hollywood film especially, exploits our negotiations with our own perceptual flux, and engages our will in ways that minister to narrative desire, to the body English that makes us try to see things as acting the way we want them to act.

I think that what we have here is a natural analogue to Newcomb's Problem. By choosing our perceptions right, we may be able to get what we want. If that's how the psychology of narrative works (through the general phenomenon that I call non-causal bargaining), then on every scale, from 1/24th of a second to two or more hours, our relation to film keeps our occasionalist testing of what we see highly sensitized and engaged. This would make film a particularly apt medium for narrative engagement (probably just about as apt as language, where I think we do a similar sort of testing).

Obviously I wouldn't confine this to Hollywood movies: Chatal Akerman's Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles is a case in point: we watch Jeanne over three days and start noting the tiny differences in what she's doing. Are they artifacts of film making or are they action? That's the question that animates our perception of the movie.

The perception of all action requires our involvement, and the more our involvement is fictional or factitious, even on the level of the most basic perception, the more it enmeshes our willing and our wishing, our desire and our engagement in non-causal bargaining.

Labels:

24fps,

aspect seeing,

body English,

Borges,

Byron,

choice,

film,

Fred Astaire,

Funes,

Hitchcock,

imperceptiblity,

Kant,

Newcomb's Problem,

occasionalism,

Red Sox faithful,

sprockets,

Zeno

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)